Let’s say you’re a biotech or academic lab that needs to do bioinformatics or computational biology at a reasonably large scale. You have a tight budget and you want to be as cost effective as possible. You also don’t want to build and maintain your own hardware, because you recognize the hidden costs baked into the time, effort, and security of doing so. Luckily, the last few years have seen a proliferation of “alternative” cloud providers. These providers can compute with AWS, GCP and Azure by doing few things really well at greatly reduced prices. My main argument in this post is that by mixing services from different cloud providers, budget and cloud can mix, despite the prevailing pessimistic opinions.

To be upfront, I believe working with one of the larger public cloud providers will make your life easier and allow you to deliver results faster, with less engineering expertise. AWS has services that cover everything a biotech needs to process data in the cloud, and the integration between these services is seamless and efficient. But we’re not going for easy here, right? We’re going for cheap. And cheap means cutting some corners and making things more difficult in the name of saving your valuable dollars.

What’s the problem with the big public cloud providers? AWS allows a team to build any product imaginable, and scale in infinitely. Need to build a Netflix competitor that can deliver video with low latency and maximum uptime to every corner of the world? AWS will let you do that (and bill you appropriately). With this plethora of features comes many hidden costs. It can seem like AWS intentionally makes their billing practices opaque, allowing you to rack up massive bills by leaving a service running or enabling features you don’t need. In the future, I’ll do a separate post on keeping AWS costs manageable. For now, just know that you have to be careful or you can be burned – I personally know several individuals that have made costly mistakes here. Even when just looking at raw compute, AWS is priced at a large premium compared to competitors on the market. You pay for the performance, uptime, reliability, interoperability, and support.

The minimum viable bioinformatics cloud

With that out of the way, it’s time to design our bioinformatics cloud! The minimum capabilities of a system supporting a bioinformatics team include:

-

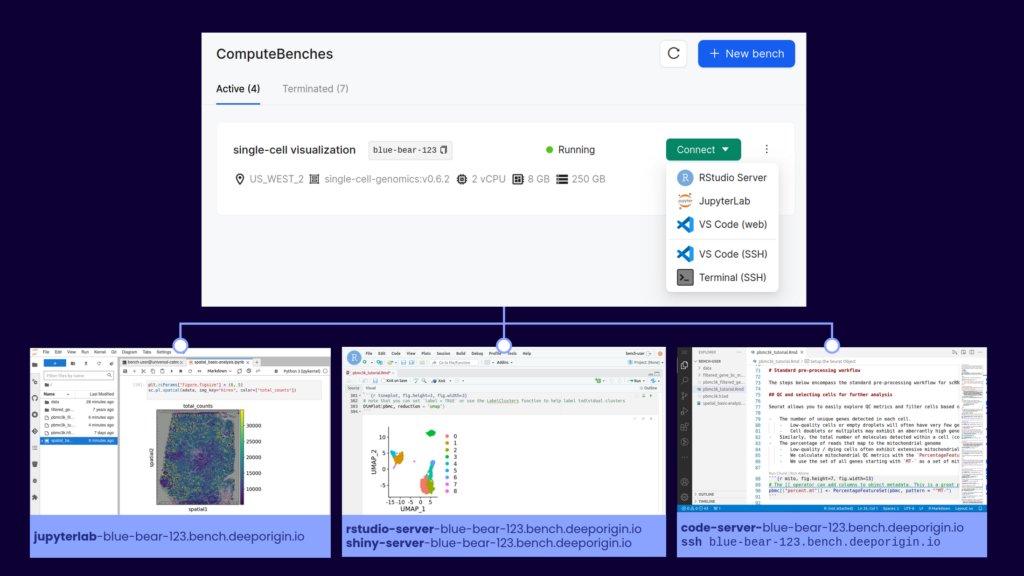

- Interactive compute for experimentation, prototyping workflows, programming in Jupyter and RStudio and generating figures. GPUs may be needed for training machine learning models.

- Cloud storage that’s accessible to all team members and other services. Ideally this system supports cheap cold storage for infrequently accessed and backup data.

- Container registries. Batch workflows need to access a high-bandwidth container registry for custom private and public containers.

- Scalable batch compute that can be managed by a workflow manager. A team should be able to easily 10-1000X their compute with a single command line argument or config change.

- GPUs, databases, and other add-ons, depending on the work the team is doing.

Where can we cut corners?

Some of the features offered by AWS matter less to a bioinformatics team.

- The final 10% optimization of latency, uptime and performance. In research, my day isn’t ruined if a workflow completes in 24 versus 22 hours – it’s still an overnight task. Similarly, an hour of downtime on a cluster for maintenance isn’t the end of the world – I always have papers I could be reading. Beyond some limit, increasing these metrics isn’t worth the additional cost.

- Multi-region and multi-availability zone. We’re not building Netflix, or even publicly available services. All the compute can be in one region.

- Infinite hot storage. I’ve found that beyond a certain point, adding more hot storage doesn’t make a team more efficient, just lazy about cleaning data up. Not all data needs to be accessed with zero latency. There has to be something similar to Parkinson’s law for this case: left unchecked, data storage will expand to fill all available space.

- Infinitely scalable compute. Increasing parallelization of a workflow beyond a certain point often results in increased overhead and diminishing returns. While scalability is necessary, it doesn’t need to be truly infinite.

With these requirements and cost saving measures in mind, here’s my bioinformatics in the cloud on a budget “cookbook”.

1: Interactive compute

There are two ways teams typically handle this requirement. Either by providing a large, central compute server for all members to share, or allow team members to provision their own compute servers. The first option requires more central management, while the second relies on each team member being able to administer their own resources.

How it’s done on AWS: EC2 instances that are always running or provisioned on-demand. You can save by paying up-front for a dedicated EC2 instance, but there’s a sneaky $2/hour fee for this service that makes it inefficient until large scales.

How it can be done cheaply: Hetzner is a German company that offers dedicated servers for 10-25% the cost of AWS. You can either configure a new server with your desired capabilities for a small setup fee, or immediately lease an existing server available on their website. These servers can have up to 64 vCPU, 1TB RAM, and 77TB of flash storage. 20TB of data egress traffic is included (which would cost you over $1800 at AWS)!

If you want to use the Hetzner Storage Box and Cloud services I mention later, you’ll want to pick a server in Europe to keep all your services in the same data center. This can create lag when connecting from the US, so I recommend using mosh instead of SSH to minimize the impact of transatlantic latency.

Where you cut corners: Hetzner servers are not as high powered as AWS EC2 instances, which can easily top out at over 128 vCPU. You can’t add GPUs or get very specific hardware configurations. Hetzner dedicated servers are billed per month, while AWS EC2 instances are billed per second, offering you more flexibility. Compared to AWS, there aren’t as many integrated services at Hetzner, and some users complain that there’s more scheduled maintenance downtime.

2: Cloud storage

How it’s done on AWS: S3 buckets or Elastic File System (EFS, their implementation of NFS). Storage tiers, and the AWS intelligent tiering service, allow archival storage to be very cheap.

How it can be done cheaply: Many companies now offer infinitely scalable cloud storage for significantly cheaper than S3. They also offer free or greatly reduced data transfer rates, which can help you avoid the obscene AWS egress fees. Two of my favorite providers are Backblaze B2 and Cloudflare R2. Both of these services can be accessed with the familiar S3 API. If this service is being used to store actively analyzed data, Cloudflare wins out. Zero egress fees make up for the increased storage cost. As soon as you egress more than you store per month, Cloudflare is cheaper than Backblaze.

Hetzner recently released Storage Boxes, which you can purchase in predefined sizes and get storage costs down to about $2/TB/month when fully utilized. The performance of the storage boxes is very high when transferring data within a Hetzner location, making this an ideal combination for low-latency data analysis.

Where you cut corners: Using storage and compute from different providers will always be slower than staying within the AWS ecosystem. Hetzner storage boxes come in defined sizes up to 40TB, and you pay for space that you’re not using. Storage boxes also don’t support S3 or other APIs that developers desire. For true backups and archival storage, it’s hard to beat AWS Glacier at $1/TB/month.

3: Container Registries

How it’s done on AWS: ECR (Elastic container registry) allows for public and private repositories for your team to push and pull containers. You pay for the storage costs and egress when the containers are pulled outside of the same AWS region.

How it can be done cheaply: DockerHub offers paid plans that include image builds and 5000 container pulls per day. The math on this one will depend on your workflow size and the need for public vs private containers.You could also host your own registry with something like Harbor, but that’s beyond the scope of this post.

Where you cut corners: Again, moving outside of AWS means you lose the integration and lightning-fast container pulls. Using DockerHub or another service is one more monthly bill and account to manage.

4: Batch workflows

How it’s done on AWS: Deploy workflows to Batch or EKS (Elastic Kubernetes Service). Compute happens on autoscaling EC2 or Fargate instances, data is stored in S3 or EFS, and containers are pulled from ECR. Batch workflows is where the interoperability of AWS services really stands out, and it’s hard to replicate everything at scale without significant engineering.

How it can be done cheaply: If on AWS, use spot instances as much as possible, and design your workflows to be redundant to spot instance reclaims (create small composable steps, parallelize as much as possible and use larger instances for less time). If you’re not on AWS, you have three options, which I will present in order of increasing difficulty and thriftiness:

- Manually deploy your workflows to a few large servers on your cloud provider of choice. If you’ve containerized your workflows (you’re using containers, right?) running the same pipeline on different samples should be as easy as changing the sample sheet. This method obviously takes more oversight and doesn’t scale beyond what you can do on a few large servers.

- Deploy your workflow to a Kubernetes cluster at a managed k8s provider, like Digital Ocean. You can use the autoscaling features to automatically increase and decrease the number of available nodes depending on your workflow.

- Deploy a Kubernetes cluster to Hetzner Cloud. Here, you’ll be managing the infrastructure from start to finish, but you can take advantage of the cheapest autoscaling instances available on the planet. I can expand this to a tutorial if there’s interest, but the basic deployment looks like this:

- Set up a Kubernetes cluster using something like the lightweight distribution k3s.

- Set up autoscaling with Hetzner so you don’t have to manage node pools yourself.

- Nextflow and other workflow managers need storage (a persistent volume claim, or PVC) with “read write many” capabilities. You can set this up with Rook Ceph.

- Modify your workflow requirements so that you don’t exceed the maximum resources available with a given cloud instance. The Hetzner Cloud instances are not as CPU and memory heavy as AWS.

- Deploy your workflow using the storage provider and container registry of your choice!

These setups obviously take more time and expertise to create and manage. Ensure that your team is familiar with the technology and the tradeoffs. If you want to deploy big batch workflows with minimal configuration, it’s hard to beat the managed services at AWS.

5: GPUs and accelerated computing

How it’s done on AWS: Get an EC2 instance with a GPU. Use GPU instances within a workflow.

How it can be done cheaply: Hetzner doesn’t offer cheap GPUs yet, but other cloud providers do, like Genesis Cloud, Vast, and RunPod. The obvious downside of this is splitting your workloads up between another cloud provider.

General advice

These tips can apply regardless of the cloud provider and services you use. Many of these came up in a Twitter thread I posted the other day.

- Use spot instances whenever you can to save ~50% on compute. On AWS, set your maximum bid to the on-demand price to minimize interruptions.

- The big cloud providers offer credits to new teams to get them on the service – I think the standard AWS deal for startups is $100k in credits for a year. They also offer grants for research teams looking to take advantage of the cloud. My best “hourly rate” in grad school was filling out a GCP credit application – about $20k for one hour of work!

- Turn your stuff off! This goes without saying, but so much compute is wasted by just leaving servers running when they don’t need to be.

- Get good at the cost exploration tools, and designate one team member to understand the monthly bill and track changes.

- Test your workflows at small scale before deploying to a big cluster.

- Use free and cheap accelerated compute available at Google Colab and Paperspace.

Conclusion

Cloud computing has made large strides in the last ten years, but for use in research, we still have a long way to go. I agree with the sentiment that we’re still early in cloud. For biotechs and academic labs that don’t have access to a university cluster (or are scaling beyond what their cluster can offer), there aren’t many alternatives to cloud computing. Unfortunately, high costs and stories of researchers breaking the bank with AWS turn many people off from these solutions completely.

My goal with this post is to outline some alternative services that biotechs and academic labs can use for their storage and compute. By being thrifty and learning some new skills, I bet cloud bills could be reduced by 50% or more. However, the integration between services in AWS is still top notch, and I hope we see more innovation and competition in this space in the near future.

Do you have experience with the services I mentioned? Agree or disagree with the recommendations, or have something else to add? Please let me know in the comments below!